Seeing Red

A thought experiment

I watched a YouTube video the other day about the “Mary’s Room” thought experiment devised by Australian philosopher Frank Jackson.

The thought experiment goes like this: Mary lives in a room. Mary has only ever lived in the room. The room contains only black-and-white objects, with no color screens, and all light entering the room has the color filtered out of it. Also, Mary is a genius. She has spent her life studying the human brain, optics, color theory, and anything else containing information about the color red. She has read everything there is to read, and been told everything there is to tell about the subject—from how rods and cones in the eye take in a certain wavelength of light and the optic nerve triggers processes in the brain, to the poetic and literary associations of the color red. One day, the tv screen inside Mary’s room mysteriously starts broadcasting in color, and shows Mary a red apple. Here’s the question: does Mary learn anything new when she sees red for the first time?

The intention behind this thought experiment is to debunk “physicalism,” which holds that “all (correct) information is physical information.” Jackson aims to demonstrate that our knowledge of things consists of more than simply “physical information” about those things—that even the most mundane experience gives us access to something ineffable and non-material (which Jackson and others call “qualia”). Mary, the argument goes, knows all the information one could read or hear about the physical characteristics and effects of redness, and yet she still has something to learn when she finally has direct experience of redness.

I’ll be honest. I don’t think Jackson really succeeds. The Mary’s Room thought experiment does not demonstrate what he thinks it does; it does not discover some incommunicable (or even non-physical) aspect of the objects of our experience.

That’s because there’s a hidden premise in Jackson’s argument, having to do with the kind of information Mary receives in her room. Consider this sentence, from the first page of the paper: “Nothing you could tell of a physical sort captures the smell of a rose.” Well, of course you couldn’t “tell” someone a scent (regardless of whether the content of what you tell them is “of a physical sort” or not); Jackson may as well be saying you can’t tell the plot of a movie by smelling it. You can still inform someone of the scent of a rose, perhaps by spraying some rose-scented perfume their direction. What Jackson calls “information” is exclusively the kind of information you can “tell”—that is, information communicated by the specific medium of the written or spoken word. In the room, we imagine Mary reading books and hearing scientific lectures on her television, accruing verbal information. But having “all verbal physical information” is not the same thing as having “all physical information.”

Anyone who has been to an art museum or enjoyed a piece of music could tell you words are one medium of expression, but not the only one. Works of art or music communicate things words don’t, and even can’t; and likewise a novel can communicate things paintings and symphonies can’t. That’s not because either is magic; it’s simply because they are different media.

The dual assertion that 1) Mary knows all there is to know about red and 2) has not seen red is, therefore, a contradiction in terms. On the terms of the thought experiment, there is one piece of information about red that Mary did not receive in her room. That missing communication is invisible to Jackson’s paper because it is necessarily not verbal. It is not something you could “tell” about red. It is not propositional. But neither is it some mysterious non-physical quality (“qualia”) hiding in the redness.

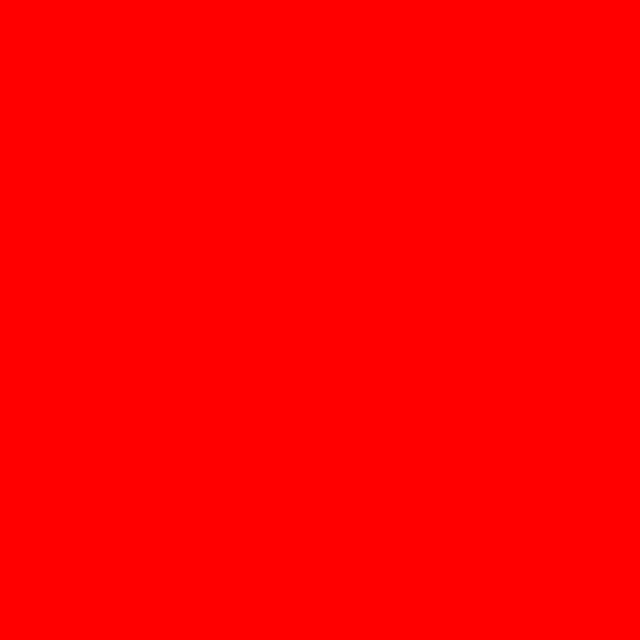

What is this piece of information, which is non-propositional, but still communicable and physical? Well, it’s this of course:

What you see above is a symbol. It communicates something about physical reality, and is itself a physical token of communication (ie, pixels displaying a specific wavelength of light). It shares that physicality with written statements about rods and cones in the eye, or about the vibrancy of a red sunset—those words are symbols too, and they also convey information about something physical. We can talk about the non-verbal symbol above using words, but by doing so we switch media, and thereby accept a different range of possibilities for what we’re able to communicate. The words we use to talk about the image above will never exactly communicate what the image does—and the image will not tell us the first thing about optic nerves. Word and image each communicate, though the content of their communication is not interchangeable. Different media convey different content. The medium is the message, you might say.

The problem with the Mary’s Room thought experiment—as originally deployed—is that it assumes all informative communication is verbal. What can’t be expressed verbally, it leaves out of the category of “information” altogether, placing it in the far broader category of “experience,” which it simultaneously renders too mysterious to discuss. What it takes to be “qualia” hiding inside the objects of human experience is actually the gap between what words can express and what they can’t—but other types of symbols can.

This is why people make art and music and study semiotics and media theory: because the range of possibilities for our communication is wider than words.

If you want to argue against physicalism, Mary’s Room isn’t a good way to do it. I don’t think the objects of sense-experience are a very promising place to look for non-material realities. We are physical creatures with physical senses; the physical is the proper mode for all our direct experience.

One last note: Mary’s Room does demonstrate the existence of a very special kind of symbol: that which is, or accomplishes, what it signifies. The image above is red, and it also communicates redness. That’s unlike the word “red,” which is a symbol removed from its referent. Stuck in her room, Mary only had symbols about red, alienated from the actual thing those symbols were talking about. But one day she receives a symbol which is red, and communicates red to her. To call it self-referential doesn’t quite do it justice; it gives Mary itself, directly, with no detours. Words sometimes act like this kind of symbol too (yelling “hey you!” at someone, for example, makes them the “you” the word identifies them as).

And here we should give Jackson some credit: there is something mystical about this kind of symbol. It communicates without any of the alienation of the Left Behind videotape or the New Atlantis floating Bible we talked about before. This symbol resists objectification and commodification, because it can’t be disentangled from its source or its referent. Self-communicating or self-accomplishing symbols are worth keeping an eye out for.

Next time, another art museum trip.