'We Might End Up With Something Revelatory'

What kind of thinking do we do on the internet?

Welcome to the second-ever edition of Symbol Factory! This and several subsequent installments will expand on the question of what in the world I’m doing here.*

A major point of inspiration for this project is Umberto Eco’s novel Foucault’s Pendulum, a book about what it looks like to think with a computer.

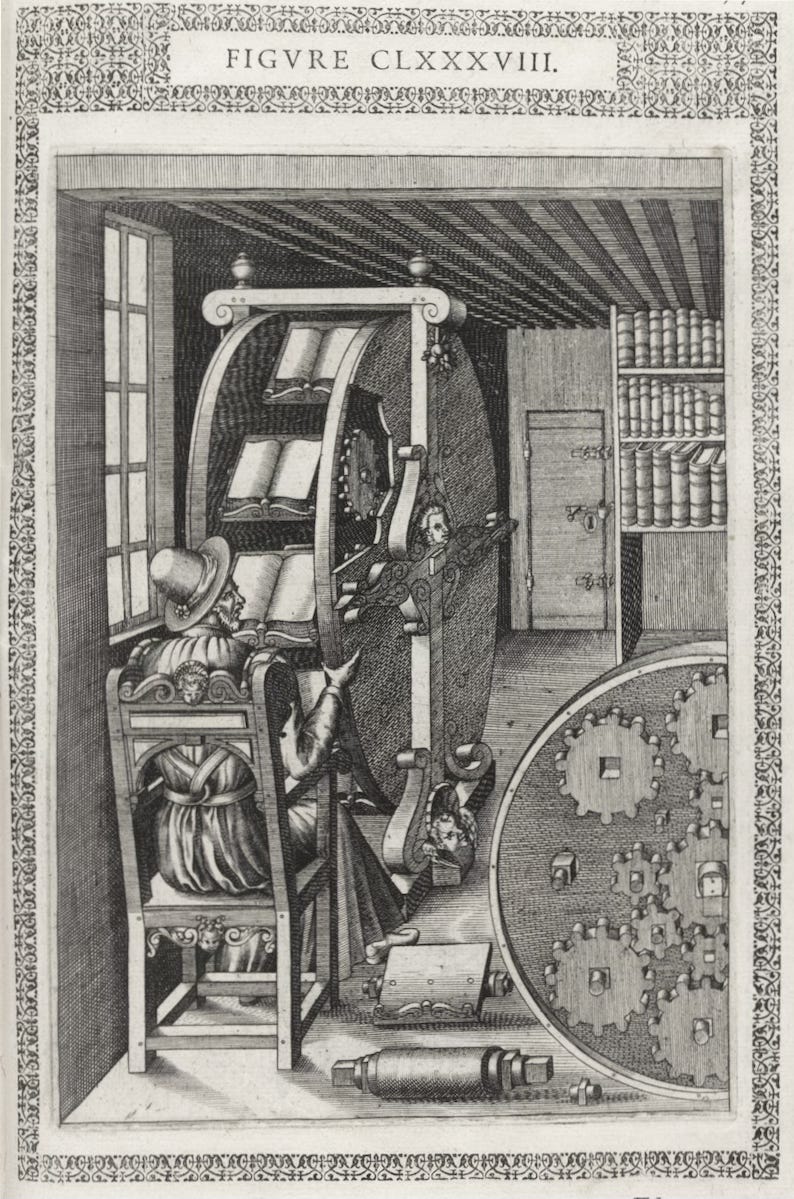

Here’s the novel’s premise: three editors get too bored for anyone’s good. The publishing house they work for starts an imprint for occultists and conspiracy theorists. Manuscripts flood in. Around the same time, the trio get a brand-new office computer that can run basic programs and has a word processor (the novel’s from 1988, and I imagine this was very impressive at the time). They name the computer “Abulafia”—after a late medieval Sephardic cabalist whose method of mysticism involved mentally forming, turning, and remixing letters of words in the Torah—and begin playing around with it on company time.

Our intrepid editors decide that with help from Abulafia, they can come up with a better, more comprehensive conspiracy theory tying together all the world’s strange happenings than their occultist authors (whom they nickname “the Diabolicals”) can. So they begin by extrapolating an alternate history based on the Diabolicals’ most common claims. When they get stuck, they turn to the computer:

What if…you feed [Abulafia] a few dozen notions taken from the works of the Diabolicals—for example, the Templars fled to Scotland, or the Corpus Hermeticum arrived in Florence in 1460—and threw in a few connective phrases like ‘It’s obvious that’ and ‘This proves that’? We might end up with something revelatory. Then we fill in the gaps, call the repetitions prophecies, and—voilà—a hitherto unpublished chapter of the history of magic, at the very least!

They enter these “few dozen notions” as inputs into their computer, run a program that randomizes them, and read the rearranged outputs as missives from an oracle. They also throw in some “neutral data” like “the koala lives in Australia” and “Minnie Mouse is Mickey’s fiancée” because, “If we admit that in the whole universe there is even a single fact that does not reveal a mystery, then we violate hermetic thought.”

What the computer gives them is an ever-growing compendium of knowledge, real and fake, told as a single story with only the thinnest imitation of an internal structure. Abulafia’s algorithm discovers no preexisting connections or resemblances between the statements it receives; it simply declares that such connections exist. That’s enough to make its story convincing, as the editors soon discover:

Any fact becomes important when it’s connected to another. The connection changes the perspective; it leads you to think that every detail of the world, every voice, every word written or spoken has more than its literal meaning, that it tells us of a Secret.

The way our computers organize and present information, Eco suggests, has much in common with how the Diabolicals—those conspiracy theorists and crackpots who see everything as a secret sign of something else—do it. The world appears to the editors and the authors alike as a big Kantian pile of unorganized phenomena, waiting to be arranged into an order. From that pile of opinions, conjectures, and genuine facts, Abulafia’s simple little algorithm makes order, or a parody of order, simply by putting them together into a single “feed”—with fact printed next to falsehood printed next to conjecture printed next to “Minnie Mouse is Mickey’s fiancée.” The editors’ brains fill in the gaps, imagining and improvising substance to the connections Abulafia declares.

We at Symbol Factory are very interested in that process of identifying and imagining connections based on what you see juxtaposed on the computer. In his documentary Can’t Get You Out of My Head, Adam Curtis offers a succinct summary of this way of approaching the world. He describes Louisiana District Attorney/JFK conspiracy theorist Jim Garrison’s procedure for investigation thus:

You didn’t bother with meaning or with logic…because that will always be hidden. Instead, you look for patterns, strange coincidences, and links, that may seem to have no meaning, but are actually telltale signs on the surface of the hidden system of power underneath.

This way of thinking is not quite deduction nor induction; those involve moving either up or down, so to speak, between specific facts and general principles. Garrison and Abulafia’s method is more like moving side to side, drawing lines between perceptions and facts and opinions. Do it long enough, and a greater picture will emerge—at least, that’s the hope.

This method of stitching together links and resemblances (in a word, thinking like a Diabolical) has its risks, of course—the editors in Foucault’s Pendulum start acting as if their conspiracy theory is true, with disastrous consequences. For Curtis, Garrison’s conspiracy thinking represents a kind of despair about the possibility of political change, because it starts with the assumption that the mechanisms that truly move the world are, for one reason or another, hopelessly obfuscated. On a more abstract level, it gives rise to a lot of anxieties about finding something “objective” to ground your symbols in—if everything refers to everything else, how could there be something to which they all ultimately refer? If we only move “side to side,” from symbol to symbol, how can we ever move “down,” to an underlying reality?**

Some situations, however, make this way of thinking unavoidable—namely, when a new media technology brings a deluge of (seemingly) unorganized symbols.

That is, when the internet happens. The internet is a pile of (again, seemingly) unorganized symbols, poured into your lap. On almost every website, especially ones like Substack, and across many websites, news stories and personal posts come intermixed with ads, entertainment, gossip, image and video and sound and fury. While there are some common entry points to this pile of symbols (Google search, for example), they have no clear structure apart from largely inaccessible “algorithms” that choose the order of symbols with a greater or lesser degree of randomness. And indeed, even those entry points to the internet (search engines, aggregators, social media platforms) do their best to make ads look like authoritative sources; make clickbait look like news; make rage fuel look like friendly conversation. It’s on you to make it make sense, to structure what you’re seeing, if only enough to navigate life online.

At the same time, the internet suggests to us that it might all fit together. Everything comes “linked” to something else. (If you’ve ever played the Wikipedia game, you know what I’m talking about.) The symbols tell us they refer to other symbols: a tweeted opinion links to a news article, an ad links to a store page. In another of his documentaries, Curtis highlights the internet aphorism “if you liked that, you’ll love this.” And then there’s the fact that, in a social media feed, any given thing may be juxtaposed next to anything else. Intended or not, it’s an invitation to see a connection between the two, like a printout from Abulafia. You move through this universal network from link to link, never reaching a higher or lower vantage point but ever more assured that everything is connected somehow.

It’s a kind of thinking that we’ll be doing a lot of at the Symbol Factory. Yes, it has its risks. But the fact is, there are coincidences in this world; there are links between phenomena and political events and fields of study that we might be tempted to keep siloed. The world is interconnected, and more so every day. Thinking in terms of connection, resemblance, and coincidence may be our only hope of conceptualizing a world where every economy depends on every other, where people across the world can speak to each other and sell to each other and worship together and collaborate on causes and influence each other’s national politics. Love it or hate it, the internet is only teaching us how to navigate the world it itself has made.

Then again, how much of this is truly unique to the internet? Check your inbox next week, and we’ll talk about it.

*I promise they won’t all be this long.

**a question to be addressed in future installments of Symbol Factory!

subscribed :)